Norway – On the outcome of the bourgeois election circus

We share hereby an unofficial translation of Tjen Folket Medias statement on the outcome of the elections in Norway:

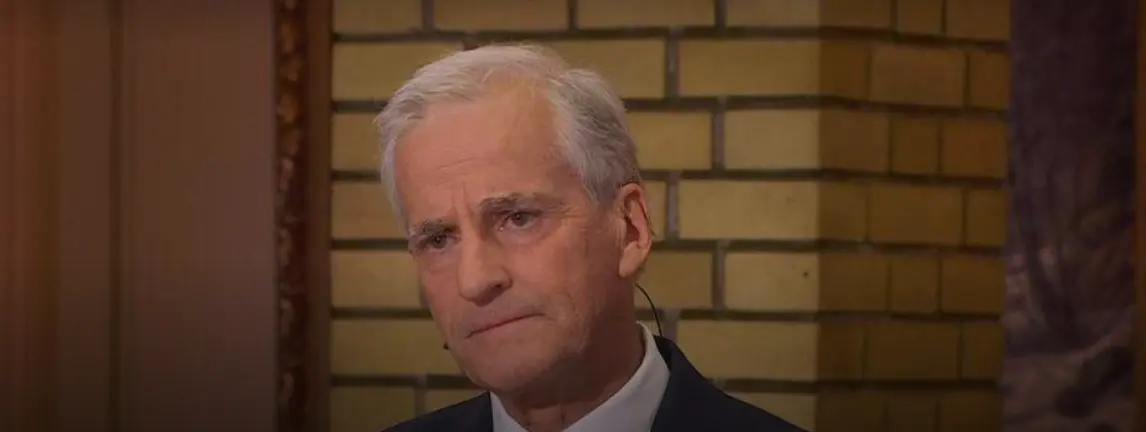

Jonas Gahr Støre (Labor Party) may continue as prime minister after the election, but The Progress Party is the big winner. The result gives a more fragmented parliament and a more unstable parliamentary situation, after the Labor Party’s fourth worst election in 100 years.

The Labor Party became the largest party in the parliamentary elections with 28.2 percent of the votes. With the help of four other parties, Støre’s government has the support of a narrow majority in the new Parliament. The “left wing” in the parliament (Labor Party, Center Party, Socialist Left Party, Green Party, and the Red Party) has a total of 87 seats, and a majority requires 85. Bourgeois commentators call the new majority a “tutti-frutti coalition.”

Increased voter turnout, but…

The 78.9 percent turnout in this election represents an increase since 2021, when it was 77.2 percent. Of the last 20 elections (1949-2025), this is roughly average. Turnout has been higher 10 times and lower 9 times. Voter turnout is the highest since 1989, i.e. higher than in the last 8 elections (1993-2021).

Our analysis is that several important factors may have contributed to reversing the trend of lower voter turnout: (1) The Progress Party has more than doubled its support, thereby mobilizing many “protest voters”; (2) record-high contributions to parties and election campaigns have increased propaganda to vote; (3) a record number of advance votes – from 1.6 million to 1.9 million; (4) mobilization to “vote for Palestine,” which may have increased support for parties such as the Socialist Left Party, the Red Party (Rødt), and the Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne), especially in constituencies that have historically had low voter turnout, and (5) some progress for the Red Party, especially in Finnmark – which has certainly also mobilized some “protest voters” from among those who previously refrained from voting.

In addition, there has been a targeted campaign to increase voter turnout in districts and constituencies where it has previously been low, such as Fjell in Drammen and Stovner in Oslo. Although the increase is moderate, the Socialist Left Party in particular has made gains in these very constituencies. During the election campaign, the Socialist Left Party has received support from both the Palestine Committee and Islam Net (muslimerstemmer.no), which have campaigned to vote “for Palestine.” Islam Net spokesperson Fahad Qureshi has even called it a religious duty for Muslims to vote in this election because of the genocide in Palestine, and has recommended voting for the Socialist Left Party.

All in all, these votes have not only contributed to a slight increase in voter turnout – they have also helped Jonas Gahr Støre remain prime minister. Clearly forgotten are the scandals surrounding the oil fund’s investments in Israel and Støre’s repeated statements that Israel has “the right to defend itself.” Also clearly forgotten is that all these parties (Labor Party, Socialist Left Party, Green Party, and the Red Party) have labeled Palestinian resistance as “terrorism.”

In general, there has been very strong pressure to vote in this election. We do not believe that this will change the long-term trend of declining voter turnout among the poorest, but it shows that this development is not continuing without counteracting tendencies. This is an expression of the historical law of uneven development. It remains to be seen whether the same type of pressure can work in the next election. We assume that many will be disappointed when they see what their vote will be used for in the coming years, with welfare cuts and military rearmament.

Bourgeois commentators speculate that a “close election” and “uncertain international situation” contributed to the relatively high voter turnout. This has certainly characterized the election campaigns of the various parties and “blocs” in bourgeois politics, and clearly contributed to the pressure to vote.

Nevertheless, over 820,000 people still abstained from voting. This represents over 20 percent of those eligible to vote. In addition, there has been a record number of blank votes in this election: 26,000, an increase of approximately 6,000. With the blank votes, there are over 845,000 voters who have chosen not to vote for any of the parties. By comparison, the Labor Party, received approximately 906,000 votes.

We assume that most of those who do not vote are still to be found among the poorest in the working class.

Record amounts of money for election campaigns

The conservative political parties, all of which are represented in the Norwegian Parliament, received record donations in 2025 – and also the year before (2024) – for an election campaign characterized by large investments to get people to vote. The previous parliamentary election in 2021 was also a record year for financial support to the parties. Now this record has been surpassed by this year’s donations.

The parties have received 152 million [NOK] in contributions in 2025, and 127 million in 2024. This year’s contributions represent an increase of over 50 million compared to 2021. In addition, there are private election campaigns, both with physical advertising and advertising on social media, where people such as investor Christen Sveaas (Kistefos company) and the LO union Fagforbundet have bombarded voters with their posters and films.

The Labor Party government continues on a weakened foundation

The Labor Party is set to continue in government alone after this election. This has already been confirmed by the party leadership. What is new is that the Labor Party can no longer base its budgets and decisions solely on the Center Party and Socialist Left Party. After this election, they also need the Red Party and the Green Party to secure a majority. This means that the Labor Party is dependent on four other parties for a majority for its budgets – unless it turns to the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party, and the Christian Democratic Party instead.

In other words, the Norwegian state continues to have a weak parliamentary government. Although the Labor Party increased its support by about 2 percent in this election, this means that the government still has less than one in three voters behind it, and that from now on, this government is dependent on even more parties to obtain a majority for its policies in the parliament. The historically unpopular government has become marginally less unpopular, but this may prove to be a Pyrrhic victory: the temporary victory in the election may turn into a series of defeats in negotiations over the next four years.

The Labor Party has had its fourth worst election since 1924. Only in 2021, 2017, and 2001 has support been lower—unless we go back to 1924, when the party had just experienced two splits in three years. It is interesting how the Labor Party leadership is now celebrating an election that, in a historical context, only confirms the Labor Party’s decline.

Regarding the parliamentary situation, political commentator Lars Nehru Sand on NRK says that where others see problems, Støre sees opportunities. Even though the government needs four parties to secure a majority “on the left,” the government has made several attempts over the past year to form other majorities. For example, the Labor Party negotiated with the Liberal Party for a majority for the “salmon tax” in 2023, and this spring they invited the Conservative Party and the Progress Party to a “tax settlement.” Several years ago, Støre also attempted to explore the possibilities for cooperation with the Christian Democratic Party and the Liberal Party, which aroused fury among the leadership of the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (Fellesforbundet).

In other words, Støre wants the opportunity to “slalom” in the parliament, seeking majorities on all sides when it suits the government. In one sense, it may appear that the parliament is gaining more power, but in essence this means that the government is actually gaining greater room for maneuver. Nevertheless, it is not as easy as it may sound. For example, there are forces within the Center Party that want closer cooperation with The Conservative Party and The Progress Party, and these may gain strength internally after The Center Party’s miserable election results this year.

Nor should we completely rule out the possibility that The Labor Party may in the future follow in the footsteps of its sister parties in Denmark and Germany, which are currently in government with The Conservative Party’s sister parties (the Danish Left and the German CDU/CSU, respectively). This could be a possibility, but historically it would be a minor political earthquake in Norway, and the parliamentary system in Norway is also different from that in these countries. There, a government must gather an active majority in the national assembly in order to take office, while in Norway it is only necessary not to have an active majority against you. It is also not possible to call new elections in Norway. This makes it more likely that there will be various minority governments that can seek majorities in all directions on specific issues and budgets.

Regardless of what happens, the government will be vulnerable in the coming period, as it is based solely on The Labor Party’s 53 out of 169 representatives in the parliament. Unpopular issues could quickly turn the majority against the government, opening the door to cabinet questions or embarrassing defeats in Parliament. The Progress Party leader Sylvi Listhaug, the big winner of the election, said on election night that it will be “interesting to follow” this situation going forward.

The Progress Party election winner – doubled its support

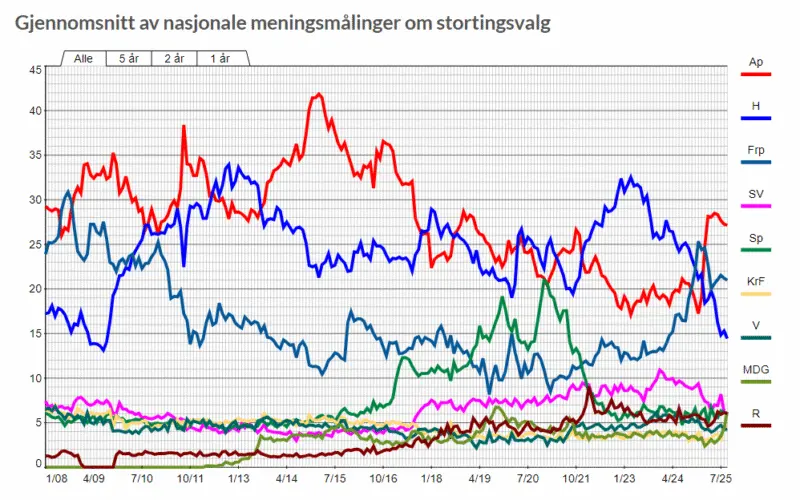

The Progress Party more than doubled its support and became the second largest party with 23.9 percent – up from 11.6 percent in 2021. This is the party’s best parliamentary election ever, and we have to go back to 2005 and 2009 to find similar figures, 22.1 and 22.9 percent respectively. At that time, The Progress Party was the largest party on the “conservative side,” and it was not until a few years later that The Conservative Party regained this position.

Several commentators say that under Sylvi Listhaug, The Progress Party has its sights set on the 2029 election and the possibility of having its first prime minister. Thus, their top priority in this year’s election campaign has not been to rally their alliance partners around them, but rather to show how the party stands out and dethrone The Conservative Party as the natural focal point in a potential new government coalition.

They have succeeded well in this, with some help from Støre and The Labor Party, who singled out Listhaug and The Progress Party as their main opponents in the election.

The big losers in the election

The biggest losers in the election were The Center Party and The Conservative Party, which lost 7.9 and 5.7 percent of the vote, respectively. Together with The Progress Party’s gain of 12.3 percent, this illustrates the ever-increasing fluctuations in support for the parties. It is barely five years since The Center Party had poll ratings of over 20 percent. Now they ended up at 5.6 percent.

The Center Party thus ended up once again in the company of the “barrier parties.” Now there are six parties in the parliament that are between 3.7 and 5.6 percent—the Liberal Party, The Christian Democratic Party, The Green Party, The Red Party, The Socialist Left Party, and The Center Party—and thus dangerously close to the 4 percent barrier. With a few small changes, the election result would have been completely different. If The Left Party (3.7) had received 0.3 percent more and The Greens (4.7) 0.7 percent less, The Progress Party, The Conservative Party, The Christian Democratic Party, and The Liberal Party could have started negotiations on a new government today.

This confirms the trend towards a more unstable political situation in this election.

For The Conservative Party, the election was a minor disaster, with only 14.6 percent of the vote.

“The failure of others is not to be despised either.”

Incidentally, The Green Party and The Christian Democratic Party both did relatively well in the election. These parties celebrated and, in the weeks leading up to the election, were touted as winners by the conservative media. Now that the results are in, we see that both parties only just managed to exceed the 4 percent threshold. The Green Party with 4.7 percent and The Christian Democratic Party with 4.2 percent. This makes the ecstatic celebrations seem somewhat contrived.

Nevertheless, both parties are satisfied, as they had both been declared virtually politically dead over the past four years, often with poll ratings in the low 2 percent range. Both parties have also been plagued by internal problems and low support. Two Christian Democratic Party leaders have resigned amid scandals over the past four years. This time around, both parties gained some ground by encouraging “tactical voting.” They argued that a vote for one of these parties could mean more, because small margins determine whether they cross the threshold and thus whether they get a group of 2-3 or 7-8 representatives in the parliament.

Several billionaires have made large contributions to The Christian Democratic Party in the hope that this could secure a new government led by The Conservative Party and The Progress Party. Almost a third of The Green Party voters have told pollsters that they voted “tactically.” The Greens have guaranteed their support for Støre as prime minister, and more voters have become convinced that they will get more out of voting for the Greens than, for example, the Labor Party or The Socialist Left Party. The Greens thus follow The Red Party as one of the first new parties to break the threshold in the last fifty years.

The trend toward fragmentation of conservative politics continues.

The Red Party made some gains in the election, reaching 5.3 percent, its best result ever. They did particularly well in Finnmark and in several old industrial municipalities. On the other hand, the party did poorly in the school elections, with only 2.8 percent. The party has thus succeeded in appealing to new groups with its focus on social security, trade unions, free dental care, and the fight against wind turbines, but it does not seem to have much appeal among young people.

The Socialist Left Party, on the other hand, fell back 2.1 percent to just 5.5 percent, making this one of its worst elections ever. Several conservative commentators point out that The Socialist Left Party, The Red Party, and The Green Party have appeared very similar in this election campaign. Despite the help of “Vote for Palestine” campaigns, the party has not been particularly successful in distinguishing itself or appearing as a safer choice than its closest competitors.

Finally, The Liberal Party ended up below the threshold this year, with only 3.7 percent of the vote. Norway’s oldest party has not even been a shadow of its former self since 1969. The party, which previously brought together a broad national-democratic conservative coalition in its ranks, lost the farmers to the Center Party and the free churches to the Christian Democratic Party. In the 1970s, they lost large parts of the urban intellectuals to the Socialist Left Party and the “ML movement.” Today, they are feverishly trying to hold on to some teachers, “entrepreneurs,” and small capitalists, and in recent years they have marketed themselves as the most ardent supporters of NATO weapons for Ukraine and more sanctions against Russia. This has not brought the party success, on the contrary.

Opportunities and tendencies

Many commentators have called this election campaign both boring and fragmented, despite the “excitement,” “even polls,” and major changes since winter—when the Labor Party had poll numbers around 15 percent. They point out that the bourgeois public is more divided, and that voters’ perceptions of reality and the election circus are more varied than before.

You don’t need a crystal ball to predict that the next four years in Norwegian conservative politics will be marked by more turmoil and instability. It would also be historic if The Labor Party succeeded once again in turning adversity into progress, and thus the stage is set for a change of government by 2029 at the latest – with a real possibility of Sylvi Listhaug becoming prime minister. Admittedly, everything up until January 2025 indicated that this year’s election would result in a new government, a prediction that Støre succeeded in disproving, but the likelihood of him succeeding again is very low.

On the one hand, Listhaug is portrayed as controversial, but on the other hand, she has continued the integration of The Progress Party into “the good political company.” She has served in government before, and her political role models are clearly found in the US and perhaps also in Italy, where the old Mussolini admirer Meloni is now prime minister. Looking at other countries, it is therefore not impossible that Norway could also have a more “Trump-like” prime minister.

In any case, it is not the political game in the parliament that determines how Norway or the world will develop. We live in a time of a record numbers of wars, with ever stronger national liberation struggles on several continents, with peoples wars developing and being prepared, and with a deeper and deeper general crisis in imperialism. The class struggle will intensify in Norway in the years ahead, especially when record-high defense budgets are to be financed by even more cuts in the welfare of the masses.

Around the next corner, moreover, lurks a new crisis of overproduction. If this is not postponed by major wars, it will probably occur between 2028 and 2032. If the historical economic trend after World War II continues, this economic crisis will be even deeper than the previous one (2020) – a crisis from which many countries have still not recovered. Across the Third World, many countries are still affected by the “financial crisis” of 2008. Bureaucratic capitalism in these countries is in a state of permanent crisis and revolutionary situation. It is the people, and only the people, who write history, and what happens in the decades ahead will be decided by the billions of people in the oppressed nations, not by the bourgeoisie’s circus performances every four years.

It remains to be seen what major international events will shape Støre’s second term in office, and whether he will succeed in exploiting them to his own advantage, as he has exploited Trump’s re-election and even the genocide in Palestine. With Stoltenberg already being touted as the man to breathe life into The Labour Party’s election campaign in 2025, the outlook is not promising for Prime Minister Støre. By the next election, he will be 69 years old and, if he survives his term against all odds, will become Norway’s oldest prime minister in at least 100 years. In that case, he would be a fitting embodiment of the situation of Norwegian imperialism.

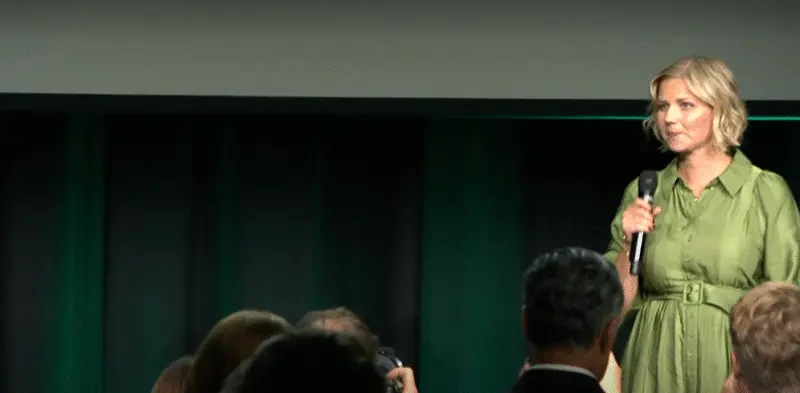

Election commentator Tone Sofie Aglen at NRK states that Støre can rejoice now, but that “everyday life will be anything but a party” for the prime minister. We are certain that the working class and the oppressed peoples of the world, as well as the other contradictions of imperialism, will fulfill Aglen’s prediction to the fullest.