Chile – El Pueblo: Notes on Fascism and Corporatism – Part I

We hereby share an unofficial translation of an article from Issue nº100 of the newspaper El Pueblo from Chile.

Notes on Fascism and Corporatism

(Part I)

For several years now—and even more so recently—accusations of fascism have been leveled at José Antonio Kast. These accusations are largely justified, as this individual’s own statements and credentials characterize him as a fascist. Part of the problem is that fascism and the corporatization of society have in Kast just one of their representatives, one who knows how to use the old “representative democracy” and its rules. The most serious problem begins with those who stand behind the judge shouting, “There goes the fascist!” There he goes!“ These people, disguised as democrats or socialists, hide their corporatist positions but end up staunchly defending the same 1980 Constitution they previously criticized, and they try to present themselves as our ”heroes” without heroic deeds or our bourgeois democrats without bourgeois democratic revolutions.

By Juan Segundo Leiva Popular Research Center

To understand fascism, it is necessary to understand what the State is and the nature of its classes. Marx argues that “the origins of States are lost in a myth, which must be believed, but which cannot be discussed.” For his part, the great Lenin stated that “the problem of the State is one of the most complicated and difficult, perhaps the one in which bourgeois scholars, writers, and philosophers have sown the most confusion.”

For Lenin, the State is organized violence. He says that maintaining a regime of exploitation is impossible “without a permanent apparatus of coercion,” without “a machine for one class to repress another.” And he further clarifies this point: “This machine can take various forms. The slave-owning State could be a monarchy, an aristocratic republic, and even a democratic republic. In reality, the forms of government varied extraordinarily, but their essence was always the same: slaves had no rights and remained an oppressed class; they were not considered human beings.”

Lenin clarifies that “any State in which private ownership of land and the means of production exists, in which capital rules, however democratic it may be, is a capitalist State, a machine in the hands of the capitalists for the subjugation of the working class and poor peasants. And universal suffrage, the Constituent Assembly, or Parliament are merely a form, a kind of promissory note, which does not change the essence of the matter.” He insisted that the form of State domination may vary, “but power is always, essentially, in the hands of capital, whether or not there is restricted voting or other rights, whether it is a democratic republic or not; in fact, the more democratic it is, the more crude and cynical is the domination of capitalism.” “Capital, once it exists, dominates the entire society, and no democratic republic, no electoral rights can change the essence of the matter.” This becomes more acute and unsustainable under imperialism.

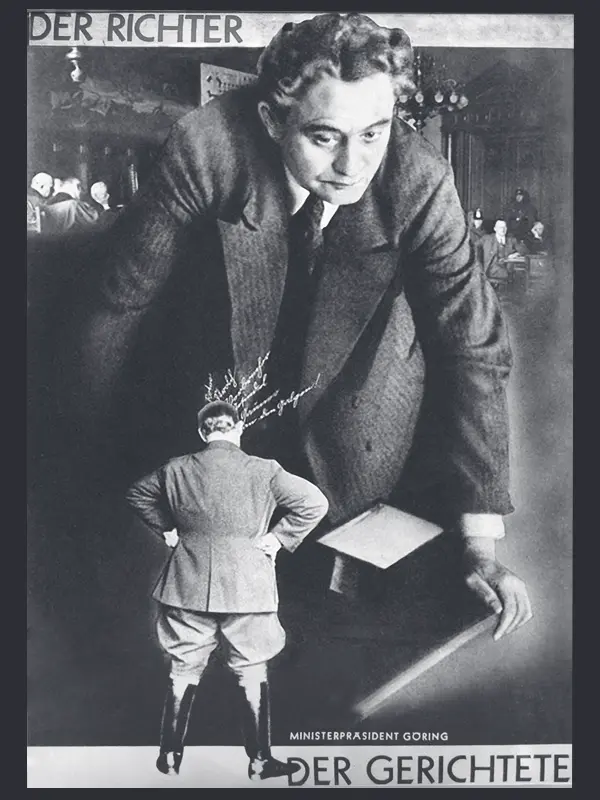

We will take up Chairman Gonzalo’s approaches to this important issue. He points out that Lenin also saw that, with imperialism, the armed forces became much more powerful and the entire economy became militarized, that the bureaucracy grew immensely and the apparatus became increasingly repressive, but he did not have the opportunity to see fascism. Fascism will emerge as a necessity of the bourgeois State to stop the revolution. Fascism does not raise its head or emerge in Russia because the proletarian revolution triumphs. As the revolution unfolds in Europe, fascism will appear on the scene and develop a fierce “struggle against parliament until it crushes it.” It is important to note that Marx, long before, had already formulated that the bourgeois system is closely related to the strengthening of executive power to the detriment of parliamentary power, which is declining. This strengthening of the executive is nothing other than its growing reactionary nature.

It is extremely important to emphasize the fact that a State is always a dictatorship. For this reason, the experience of authoritarian governments is a phenomenon that predates fascist regimes. Similarly, regimes based on terror predate fascism, therefore terror—despite their sophisticated use of terror—is not one of its main characteristics.

Some typical features of fascism and corporatism can be found earlier. Marx, always a visionary in many things, analyzed the phenomenon of Bonapartism. His book “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte” is a rich source of political concepts that contribute to understanding fascism and the reactionarization of the State. In this sense, Bonapartism is related to the fact that the class struggle itself generates its “heroes,” that is, characters, often grotesque, who eventually become the saviors of the moment, in particular the saviors of the ruling classes, as their representatives. These are the führers, the “leaders.” This is the case, to mention a few, in Chile or Peru, Argentina or Uruguay in the 1970s and 1980s, when fascist military dictatorships, with their respective “leaders,” ended up, through coups d’état, overthrowing the “democratic representative” regimes that were already mired in deep crises and, as we pointed out, were becoming insufficient for the revolutionary rise of the working class and peasant masses.

In the case of the rise of fascism in Germany, it is important to understand the impact of the October Revolution and the failure of Germany’s own proletarian revolution in 1919, which was an aborted revolution. The German Social Democrats (revisionists at the time) came to power under the protection of Hindenburg serving the established order and resorting to the army to crush the German revolution and maintain the old order. This paved the way for the rise of Nazi-fascism.

After their rise in the decade of 1920, Hitler and its Party conquered a bigger influence, supported by the international and German financial bourgeoisie, even the one from United States. They aimed to contain revolution and communism, as well as to act against the Soviet Union. It was the ongoing counterrevolution.

However, the origin of fascism lies in Japan. “Action is polarized,” says Chairman Gonzalo, “revolution and counterrevolution, and bourgeois forms and liberal ideologies are insufficient to contain the revolution, hence the need for fascism.” Since the beginning of the 20th century, militaristic sectors have been waging a fierce struggle against the Japanese parliamentary liberals, while at the same time the rise of the Japanese labor and peasant movement sowed terror among the imperialists and monopolists (zaibatsu). This determined an outcome in favor of the militarist “statists,” the crushing of parliament, and the defeat of the workers and sharecroppers. This is to mention just a few of the examples that abound in world history.

Fascism is not the same everywhere; it takes specific forms depending on the historical and political conditions in which it develops and the degree of development of the revolution it faces. It can even coexist with parliament for a time, which creates a dilemma for some of its representatives. Fascism, despite its specific historical differences, has general characteristics that are common to all forms: it sweeps away everything that is bourgeois-democratic, it promotes nationalism (chauvinism), it uses social demagogy, a supposed struggle against the rich (or the rich take care of themselves), grand offers to the masses (the “radical change”).

An important leader of the Communist International, George Dimitrov, considers fascism to be a State that represents and defends the interests of the financial bourgeoisie (the imperialist big bourgeoisie), introducing fascist criteria of denial and rejection of democratic liberal principles, rejecting the parliamentary bourgeois order to promote corporatism, and which also uses terror, soft politics, and hard politics. With regard to terror, what fascism does is develop more violence as an instrument of paralysis and domination, in order to achieve its objectives of applying its fascist goals and the corporatist order (political objective). This is why a key issue in understanding fascism is that it cannot be characterized only by terror, but also by the denial of bourgeois freedoms.

As a way of confronting the rise of people’s protest and revolution, and when democratic-representative forms are no longer sufficient to contain this, the reaction attempts to implant the fascist regime, the corporate State, the vertical organization of society based on the fascist trinity: businessmen-officials (or technocrats-workers), with a political centralization of power in the Executive.

Every State is a dictatorship. This dictatorship can operate, as it has since the 20th century, in the form of representative democracy or in the form of military governments. It can do so at crucial moments or when it has the urgent need to defend or develop the prevailing order of exploitation. The big landlord-bureaucratic State, such as the Chilean State, oppresses the people, especially workers and peasants, strikes at the petty bourgeoisie, and restricts the middle or national bourgeoisie. This joint dictatorship of two classes (big landlords and the big bourgeoisie), its system of government, whether representative democracy or corporatism, and the politics that guide it, demoliberal or fascist, respectively, exploit and oppress the people.

All this becomes more complex when revisionists (bourgeois workers’ Parties) develop a fascist political conception in practice and seek to corporatize society. In this sense, the false Communist Party that governs China today is a sham for many.

After the counterrevolutionary coup in 1976, the glorious Party founded by Chairman Mao Tse-Tung became a fascist Party (as he had warned regarding the actions of the right wing within the party), and its regime, beyond the achievements that survived the workers, became a counterrevolutionary regime, a system based on capitalist restoration, with aspirations to become an imperialist power and, in the long term, a hegemonic superpower at the global level. To this end, it has had to develop fascism and corporatize Chinese society. These are issues of great relevance to understand at the present time.

(To be continued in a future edition)