Semi-feudal features in the Colombian Caribbean

We hereby share a translation we received from an article published by Nueva Democracia.

In Colombia, semifeudal relations of exploitation are maintained, based on a capitalism driven by and serving to imperialism, mainly Yankee, which did not resolve the democratic tasks inherent to bourgeois revolutions, the main one being land democratization. Instead, as explained in the documents of the Communist International led by Lenin, it maintained that structure as the foundation of its domination:

“Capitalism emerged and developed on a feudal basis, taking on incomplete, transitional, and bastard forms, which particularly favor commercial and usury capital (…) In this way, bourgeois democracy takes a distorted and complicated path to differentiate itself from feudal-bureaucratic and feudal-agrarian elements (…) foreign imperialism continues to transform, in all backward countries, the upper feudal (and partly semi-feudal, semi-bourgeois) layer of native society into instruments of its domination. (…) Imperialism, which has a vital interest in obtaining the maximum amount of benefits with the least amount of costs, maintains, until its last instance in backward countries, the feudal and usurious forms of labor exploitation.” (IV Congress of the Comintern, 1922)

José Carlos Mariátegui, a great thinker and revolutionary Marxist from Peru, characterizes Peru (a country that shares similarities in its historical process with Colombia) as a semi-feudal society and points out that latifundium, serfdom, and gamonalismo are three expressions of this.

Latifundium refers to the concentration of a large amount of land in the hands of a few, with large properties owned by landowners and the feudal nature of that large property. According to Mariategui, this concentration of land is the basis upon which relationships of serfdom and gamonalismo develop.

Serfdom refers to the systematic persistence of pre-capitalist relations of production. Peasants do not own the land, nor do they own the labor they produce; instead, they must give up the majority of it to the landowners in exchange for the right to work or even to feed themselves. In other words, peasants are serfs who provide a service without receiving adequate wages or compensation for their work.

Gamonalismo is the political expression of latifundium. It is the absolute power that landowners have over the economic, social, and political lives of peasants, made possible only by the concentration of land.

Marxism has explained that production relations are determined by who owns the means of production. In rural areas, the largest amount of land belongs to landowners. Consequently, as feudal latifundium persist, servitude (serfdom) and gamonalismo also endure, albeit under various modalities and different names. Let’s examine some forms in which semi-feudalism is expressed in Colombia.

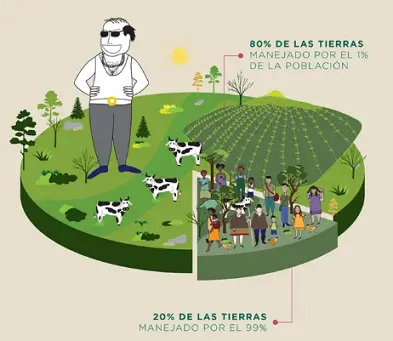

First, in terms of land concentration, Colombia is the country with the greatest inequality in land ownership in Latin America. 81% of the land is in the hands of 1% of landowners, while 19% of the land is owned by 99% of landowners. Second, concerning large feudal landholdings, according to figures from the latest National Agricultural Census (2014), of the 43 million hectares suitable for agriculture, 80% is occupied by pastures and fallow land, while only 19.7% is allocated for agricultural use and 0.3% is used for production infrastructure. Effectively, this means that in Colombia, each cow owned by large landowners has one and a half hectares to itself. In a country with classic capitalist development, such as the Netherlands, up to 140 cows are grouped per hectare of land. Thus, the land used for livestock farming in Colombia is 140 times less productive than in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, the peasant labor force faces a material limitation in their efforts to develop rural areas and achieve better living conditions: they lack land or have very little.

Certainly, the living conditions of the peasant masses are of immense precariousness. In rural Colombia, there are more than 3 million people working. According to figures from DANE (National Bureau Statics), rural unemployment in January 2025 was 8.6%. At first glance, one might say that there is employment in the countryside. But the reality is more complex. The informal labor rate in rural areas is 84.1%. This informal labor is, in most cases, not that of the successful “agricultural entrepreneur,” but rather of the peasant who has to survive on barely COP 300,000 (USD 74) per month. It is the informal labor of low wages, high exploitation, and greater profits for large landowners and the wealthy.

The “most industrialized” sectors of agricultural production are the agroindustries of banana, sugarcane, and palm, which account for only 6.9% of the total hectares with agricultural potential in Colombia. And although they are the most industrialized sectors, they bear the marks of feudalism: “in agriculture, the establishment of wages and the adoption of machines do not erase the feudal nature of large land ownership. They simply refine the system of exploitation of the land and of the peasant masses” (Mariátegui).

In Colombia, there are various examples of such perfected exploitation: for instance, in the palm agro-industry, not all workers are hired through formal contracts; they are paid based on what they do during the workday, but with a limit on the amount produced. This way, the income of the worker is controlled to ensure the permanence of the labor force: if the worker earns “too much,” the company risks the chance that the peasant will venture out on their own. Thus, by limiting the amount of work and therefore the salary, companies effectively tie down field workers.

There are also reports made by farmers’ associations and victim organizations that highlight connections between big agribusiness and the expropriation of peasant land, carried out through paramilitary groups that employed threats, murders, massacres, and other crimes against farmers and trade unionists to steal their land or suppress the struggle for better working conditions in the countryside. One example of this is the American multinational Chiquita Brands, part of the banana agribusiness, which was convicted a few years ago for financing paramilitarism in Colombia. Another example is the company Urapalma, involved in the palm agribusiness, whose several partners and board members were convicted for “the crimes of conspiracy to commit aggravated offenses, forced displacement, and land invasion, as well as established links with paramilitary groups” (Contraloría General de la Republica). The few companies convicted of links to paramilitarism are just the tip of the iceberg; many others have managed to evade justice.

Imperialist companies and grand bourgeoisie, both of whom are likewise large landowners, whether because they hold titles to large properties or because they are the ones who exploit these properties and benefit from them in practice, maintain latifindium, collude with feudal landholding power, and protect it, subjecting their workers to semi-feudal production relations.

In the Colombian countryside, those who own vast areas of land and significant capital have not developed an agroindustry that produces for the country and employs the thousands of poor peasants who only have their hands to work with and who yearn to have land to cultivate and live with dignity. The agroindustry employs a minimal portion of the rural population, and the vast majority of farmworkers are poor peasants, meaning landless farmers or those with little land who are subjected to informal and servile work as a consequence of the structure of land ownership. The colombian countryside is highly unproductive, where land continues to be, as in feudal times, a means to maintain local power, an economic and political fiefdom. The land is not used for production but primarily to derive rent from it in various ways.

The Colombian Caribbean is not immune to the previously described national reality. In departments such as Magdalena, Bolívar, Sucre, and Cesar, the vast majority of peasants do not own land, either because it has been snatched away from them by armed state and paramilitary forces or because they have never had land in their lives. These peasants are subjected to various forms of severe exploitation, all of which reproduce semi-feudal production relationships. We will present some examples that we believe are most illustrative of this phenomenon.

Farmland rental

In the Caribbean and various regions of the national territory, including some areas of Antioquia, it is a widespread and systematic practice to allow the peasant to work and inhabit a piece of land in exchange for giving away part of their labor , often nearly all of it, to the landowner. This practice has variations, but generally consists of the landowner handing over a piece of land to the peasants for a specified period so they can work it. In most cases, it is a piece of land that can only be utilized for very short periods, thus limiting the farmer to planting only temporary crops. What the landowner demands is that the land returned to them is “civilized,” meaning cleared of brush, or returned planted with grass for livestock. Sometimes, they also demand part of the harvest, and on other occasions, they require monetary payment. All the costs associated with the harvest and all the risks it entails fall entirely on the peasant. The landowner, for his part, benefits regardless of whether the peasant’s crop thrives or fails.

What has been described is, in itself, a shockingly regressive practice that embodies unpaid labor and serfdom, reflecting semi-feudal relations of production. Furthermore, it often happens that the landowner breaks the agreed-upon terms—usually made verbally—and expels the peasants from the land before they can reap the fruits of their labor. Peasants recount that a common method of expulsion employed by the landowner is to allow cattle to graze on the newly growing crops, ruining them. Alternatively, the landowner imposes new, harsher conditions on the peasant, such as demanding a portion of the harvest or money. Thus, by relying on the unpaid labor of peasants and renting out land here and there, the landowner is giving maintenance to his large property.

Charcoal

In the northern part of the Cesar department, there is another form of serfdom is linked to the production of charcoal. A peasant tell us:

“I’ve never had land. I started working hard in the fields at 16, and now I’m 64 and still don’t have a place to plant even a cassava plant. I work wherever I can find daily labor—it’s not a fixed wage, just two or three days at a time. Right now, it’s been three months with no work, nothing comes up. So now I’m just making charcoal from firewood—that’s my trade because there’s no other source of work. I gather the wood, pile it up, cover it with dirt, and burn it; that’s what is providing us with food right now… Wealthy people clear [1] the pastures to keep the weeds from bothering their cattle and allow us to collect that wood. The landowner benefits because we’re cleaning the land for him, and we also benefit because we take what we can, and that way we earn barely enough to put food on the table. They don’t pay us anything for cleaning the land; we do the work for free. We’re satisfied with the landowner—we’re grateful to him because we’re eating thanks to him. We don’t even realize the work we’re doing for him. Does he pay us? We don’t care, because we’re making charcoal—our payment comes from selling the little bit of charcoal.

To make charcoal, you work day and night—that’s the hardest-earned money you’ll ever make. You don’t sleep, you don’t rest, watching over it so the charcoal doesn’t turn to ash. We clear the land, chop down trees with an axe, gather, pile, cover it with soil, then set it on fire. After 3 or 4 days, we can start harvesting, but the whole process takes about 15 days, and they buy the bundle from us for 10 or 8 thousand colombian pesos (2.5 or 2 USD), depending on the price of the bundle, and that’s how one buys a pound of rice. I have 7 kids, all 8 years or older—every single one of them goes out to help make the charcoal.”(Own interview).

As a consequence of landlessness, the peasants in the area are forced to provide unpaid labor—a service to the landowner without receiving any payment. In this way, the landlords profit from the poverty of the peasantry and use their control over the land to subject peasants to servile relations.

Selling one’s wages

The persistence of semi-feudal relations is not merely a rural issue. In our country, backwardness is widespread, and there is a massive social stratum that cannot be absorbed as labor because there is no industrial development to employ that workforce. The situation is such that this social layer is forced to give away their labor for mere crumbs just to survive. We have seen some examples of what happens in the countryside, but now we will present an example that occurs in what our national censuses call “urban populated centers.”

In a municipality of Bolívar, cleaners, security guards, and secretaries working for local government institutions are hired on a monthly basis. These workers report: “Every time the contract is renewed—since it’s a service provision agreement [2]—they steal a month or sometimes more from us. Because we’re in need and jobs are so hard to come by, we want to keep our positions, so we keep working even if the contract hasn’t been renewed. And when they finally renew it, they postdate it, so the dates don’t match when we were actually working.”

This is a sophisticated mechanism, perfected over decades of practice. Local officials do not renew contracts on time, so the worker continues laboring for one or two months without pay. That time when the worker continued laboring without pay is billed to the state—but the money never reaches the worker’s pockets. Instead, it goes into the pockets of the officials in charge of hiring. The workers are fully aware of this practice, but given the lack of employment, they find themselves subjected to servility, allowing the local power broker to maintain this constant theft of their wages.

Furthermore, workers report that payments are consistently delayed. In response, some municipal officials have created a business to exploit employees with overdue wages: “salary buying.” Workers, with no ability to save—since they earn less than what is needed to survive day to day—are forced to “sell their salary” to these officials. The “salary buyers” give the worker 80% or 90% of their overdue pay as a kind of loan. Then, since they are municipal officials, they use bureaucratic procedures to later collect the full 100% of the salary directly. Workers report that it is the same municipal officials—the “salary buyers”—who deliberately cause their payments to be delayed. A sweet deal.

In the Colombian Caribbean, clientelism and patronage politics are practically the only way to get a job. The well-knonwn “traditional clans” handpick nearly every position within government institutions. Those who bear the heaviest burden get the worst-paid and hardest jobs: security guards, secretaries, and cleaners in state institutions that—due to the lack of industry—are the only source of formal employment. As the masses put it: in order to have one of these jobs, you have to have a good politician”

Mariátegui draws attention to gamonalismo, a distinctive feature of semi-feudalism. Undoubtedly, this trait is deeply rooted in the collective imagination in the figure of an arrogant landowner whose word is law—much in the style of Álvaro Uribe.

Precisely, the issue of gamonalismo is the issue of feudal latifundist power. The landowning class, shielded by the grand bourgeoisie and imperialism, uses every existing mechanism to impose its own law. Bourgeois law defends private property. The landowning class can seize the land of peasants using its paramilitary armies and emerge unpunished, despite infringing upon the property of others. In other cases, they may appropriate land through falsified deeds, through an entire notarial system that facilitates its fraudulent transactions, through a whole legal system that, in exchange for economic and political favors, even knowing the “illegality” of their actions, favors them legislatively and through repressive state forces that will protect their interests.

Gamonal authority stands above any bombastic “political constitution,” brimming with sweet words—a crude attempt to deceive the minds of the popular classes. Unpaid labor, of which we have seen several examples, is not written into any law, and yet it remains a systematic practice in both the countryside and cities of our country. The gamonal power has established this law. There exists a seemingly “natural” order of things, unwritten laws that weigh heavily upon the peasantry and the poor of our nation. This “natural” order is precisely the gamonal law, the gamonal authority, which dictates how things function according to its own interests.

There are places in our country where, until just a few years ago—less than a decade—the landlord still claimed jus primae noctis (the feudal practice in which the lord demands the right to sleep with any newlywed woman among his serfs). In other regions, the landlord’s overseers wield the power to physically assault peasants in broad daylight, under the complicit gaze of the police.

We recall one particularly abhorrent incident that reveals how this gamonal power materializes: the case of Osmario Simancas. As reported by Noticias UNO in 2017:

“Everything started on November 26 when Rosa Cecilia Beltrán received painful news about her son (…) they came and told me that he had been cut. Osmario was known in the area as an honest young man with great aspirations of becoming a boxer. That afternoon, the young man decided to go with his friend (…) another 14-year-old boy to play around the rural properties (…) they arrived at the Campo Alegre 2 rural property. Then a man on a horse showed up, saying that they were the ones who were stealing there. My friend told him to respect us, that we were not like that. So I said let’s go, and we left, and the man on the horse started calling for others. Osmario recounted that at that moment they ran because they believed they were going to be killed, stating that each took different paths in their escape. His friend managed to escape. I kept running, and suddenly the man was right in front of me—he swung his machete at me, and when I dodged like this with my arm, he chopped off my left arm right then. The young man said that during the attack they also cut his other hand. And then the owner of the rural property called the police to take him away (…) despite his injuries, he was always conscious and that is why he was able to identify his attackers. One of them was Edurdo Nuñez, who (…) was known as the rural property administrator. The police sided with the landowners without asking Osmario anything, even though he was already mutilated.”

This estate, located in the Caribbean, in Arjona, Bolívar, was a property under a process of asset forfeiture, belonging to the alias “La Gata”. Even today, in this part of the country, peasants denounce that “La Gata Clan” continues to control—properties that, on paper, are already in the hands of the SAE (Special Assets Society). Although the crime was reported, their aggressors remained free despite the clear evidence of their guilt. Osmario was thrown into the back of a police patrol car, and thus he was taken the entire way to town, lying there, mutilated and bleeding.

Land is concentrated in the hands of a few; peasants have no land, nor do they have the capital to rent it. There is no industry to employ their labor. Based on these conditions—especially land concentration— relations of serfdon and gamonalismo emerge as expressions of semi-feudalism: working for free for months in hopes of securing stable employment where none exists; feeling gratitude toward the landlord who steals their labor; farmland rental under the constant threat of the landlord changing the terms before harvest; being unable to plant because they lack the money to pay rent. This is the subjugation in which the gamonal power keeps the peasantry by controlling the land, forcing them into servility toward whoever can offer them “favorable conditions” amidst the lack of land, work, and poverty. This entire panorama shows us that semi-feudal relations persist in Colombia, and that it is only possible to eradicate them by abolishing the latifundium.

[1] “Zocolar” is a regional term referring to clearing for the first time an uncultivated land that is uneven. The translation uses “clear” for clarity while preserving the original meaning.

[2] A legally ambiguous instrument that frequently masks precarious employment relationships, enabling the State to evade employer responsibilities and perpetuating instability for workers.