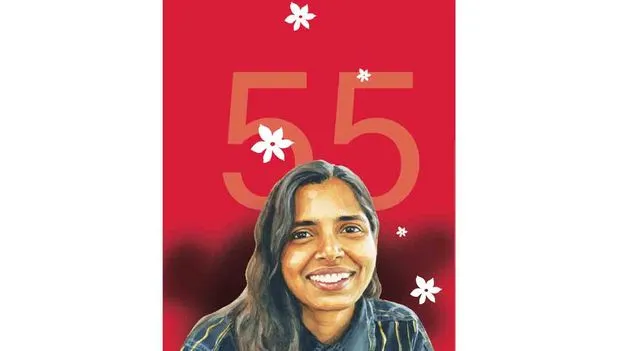

Remembering Renuka

Hereby we share a text received by email and written by the family of Comrade Renuka, to remember her on the day she would have turned 55. Comrade Gumudavelly Renuka was murdered by the old Indian State on March 31, 2025 in the forest of Bastar, Chhattisgarh.

As her relatives state, she was a prolific writer who stayed a firm communist until her last breath. With nearly 30 years of revolutionary practice, she was during 21 years living in the forests of central India, mainly in Dandakaranya.

She edited several magazines and wrote in total more than 37 texts which recently were published in two anthology volumes in Telugu, including her most important ground reports. However, among her work there are also hundreds of pieces for magazines, book reviews, poems and even interviews and translations.

Remembering Renuka

– Family Members

At home and in our village, everyone affectionately called Renuka “Chittamma.” She was born on October 14, 1970 — the only daughter of father Gumudavelly Somayya and Jayamma (Yashoda), and the middle child between two brothers. As the only girl in the family, she was dearly loved. The entire village doted on her. Unlike many other girls of her generation, she was never burdened with household chores or forced to learn cooking. Her parents gave her space and freedom — mostly, patriarchal restrictions had no place in her early life, at least within the family.

Slender and tall, Renuka was a bright student from the beginning. Because our father was a schoolteacher, our family moved from one village to another frequently. She studied in government schools across Kolkonda, Sitarampuram, Kadavendi, Mothkur, and Devaruppula, eventually completing her Intermediate at the Government Junior College in Jangaon.

At the age of 14, while preparing for her Class 10 exams, Renuka fell ill with tuberculosis. She had persistent fever, but doctors failed to diagnose the illness in time. For months, she went without proper treatment, and her health deteriorated significantly. It was only later, when Dr. Kotilingam in Warangal correctly identified the condition, that she began recovering. But the damage to her lungs had already been done. Though she regained her health, the illness had already damaged some lung tissue — and its effects stayed with her for life. She couldn’t run, couldn’t walk fast, and would tire quickly.

During her Intermediate, her elder brother became a full-time activist. After she completed her Intermediate, the family moved from Kadavendi to Mothkur. We sold our house in Kadavendi and built one in Mothkur. Around that time, our family decided to get Renuka married. She wasn’t ready — her heart was set on continuing her studies — but she couldn’t bring herself to go against her father’s wishes. He promised she could pursue her education even after marriage — so she reluctantly agreed.

But within months, her husband began harassing her mentally. Renuka, who had silently endured the pain at first, eventually opened up when it became too much to bear. The family stood by her, and the marriage was annulled. With her parents’ encouragement, she resumed her studies. Her sense of freedom returned — and with it, her journey truly began.

She completed her B.A. as an external candidate from Osmania University, and later appeared for both the M.A. (Telugu) and law entrance exams. She secured admission for M.A. (Telugu) at Koti Women’s College in Hyderabad and for LLB at Padmavati University in Tirupati. Though the distance was considerable, she chose law and moved to Tirupati in 1992.

Renuka had always been an avid reader and a lover of literature. Now, she immersed herself even deeper. At the time, the revolutionary movement in Kadavendi and across northern Telangana was gaining momentum. Renuka was inspired by the struggles — against bonded labour, for better wages, for land to the landless, and against violence on women. These struggles deeply shaped her worldview.

Her own painful marital experience had already given her a sharp understanding of patriarchy. Around the same time, feminist literature was beginning to flourish in Andhra Pradesh. Renuka read widely — but she also began asking questions: How do the communists, who are working for a new democratic and socialist society, address women’s issues? How seriously do they treat gender equality? These questions stayed with her.

It was around this time that she met Padmakka, party’s town organiser in Tirupati. One afternoon in 1992, on the recommendation of martyred Comrade Puli Anjanna, Padmakka came to Renuka’s hostel to meet her. Renuka could not have known then that this meeting would shape the course of her life forever. Padmakka patiently answered her questions and urged her to join the local women’s movement. In 1994, Padmakka was killed in a fake encounter. Renuka was devastated. It took her a long time to come to terms with that loss.

Slowly, Renuka began to combine study with activism. She worked with the organisation Mahila Shakti and began writing regularly for its publication Mahila Margam. She continued her studies while participating in organisational work — and also began writing short stories. In fact, even before leaving for Tirupati, she had submitted a story to Nalupu magazine. But the last page went missing, and the story was never published. While she was in Tirupati, she wrote several stories and shared them with literary friends who offered honest feedback and helped her improve her craft.

By 1996, Renuka was ready to become a full-time party worker. The party encouraged her to take up urban mass work. She began working on issues like dowry deaths, sexual harassment, and the everyday struggles of slum-dwellers. She led campaigns and was on the editorial board of Mahila Margam, ensuring that it came out regularly. She also became part of the Chaitanya Mahila Samakhya, a collective of women’s organisations.

During this time, Renuka would sometimes go into the Nallamala forest to meet the party leadership. She was working under martyred Comrade Lingamurthy (Krishnanna). At that time, Santosh was the Andhra Pradesh State Secretary and a member of the Central Committee. Although the name ‘Santosh’ was familiar to those from Kadavendi, Renuka had not known him personally.

It was Krishnanna and another martyred Comrade RK who suggested the idea of marriage to both of them, separately. They were given the opportunity to meet, talk and think it through. Over time, love grew between them. They married. But because Santosh was a top leader, and Renuka was engaged in public mass work, the party advised that the marriage be kept secret. Only the top leadership and a few comrades close to Renuka knew.

But their time together was short. On December 2, 1999, Santosh was killed — along with Nalla Adi Reddy and Sheelam Naresh — in a staged encounter. Renuka was heartbroken. Since their marriage had been kept secret, she couldn’t even cry her heart out in the open. She would often recall how those few years had been precious. They had shared mutual interests in books, cinema, stories, and revolutionary ideas. Santosh’s thoughts on her stories — his suggestions, his encouragement — she held close, and often spoke of them.

After this, Renuka’s work shifted to Visakhapatnam. There, she practised law while continuing her involvement in mass organisations. She mobilised poor women from the slums and stayed active in literary work under the leadership of Comrade Kaumudi, the secretary of the Visakhapatnam City Committee. Kaumudi was already well known — a revolutionary poet held in high regard within literary and activist circles. Their meetings often flowed with poetry, politics, laughter, and reflection — just as much as with organisational matters. Renuka always remembered those days with deep fondness.

But in late 2003, Kaumudi too was killed in a fake encounter. With that, Renuka’s open revolutionary life came to an end. The police were after her. She was constantly on the run. Finally, with the help of committed revolutionary supporters, she was moved to Maharashtra, and then handed over to the party leadership. From there, she went to Odisha and took charge of the Bansadhara division. She quickly learned Odia — and before long, began writing in that language too.

In 2005, she chose Shakhamuri Apparao as her life partner. Though they had not met before, both had heard of each other, and had great respect for each other’s journeys. Both had experienced pain in earlier marriages. Their new bond was based on deep understanding. But their responsibilities kept them apart most of the time. In March 2010, news of Shakhamuri’s martyrdom reached her. Another blow. Another grief to carry. But she never let it shake her revolutionary conviction.

She continued writing. In 2006, the party entrusted her with the editorial responsibility of Kranti magazine. With that, her work moved from Odisha to Dandakaranya — a land that would become her home for nearly two decades. It remained so until the evening of April 1, 2025, when her mortal body, lying still in an ambulance, along the quiet highway that runs beside the Indravati river, crossed the Godavari river, and entered the border of Telangana. It was a journey of return — across the forests, rivers, and paths she had once walked with quiet strength and unwavering purpose. The land she had given her life to, bore witness, once more, to her passing.

As for her literary work, starting with Bhavukata, she went on to write Metlameeda, Pravaham, Iddaru Tallullu, Amma Kosam, and nearly forty short stories, mostly under the pen name ‘Midko’. She also wrote a few poems under the name ‘Zameen’, and analytical pieces and books using the name ‘BD Damayanti’. In her later years, she penned powerful and evocative works such as Pachchani Batikulpai Nippai Kurustunna Rajyam, Mandutunna Gayalu, Vimukti Batlo Narayanapatna, and Dandakaranyalo Green Hunt, and so on.

Her hallmark was a writing style that was clear, brief, and direct — language that moved readers deeply, without the need for ornamentation or exaggeration. She consciously avoided stereotypical writing and never leaned on jargon for effect. Just like the way she speaks, where she would never use a word more than necessary, her writing carried the same restraint and precision. She spoke little, observed keenly, and when something felt wrong, she never hesitated to raise her voice — fearlessly and without favour. There was a quiet strength in the way she engaged with people — an affectionate demeanor, free from pretence — that drew many towards her.

From Mahila Margam to Viplavi, Viplava Patham, Kranti, Prabhat, Poru Mahila, and Lademayena Mahila, she contributed tirelessly — as a writer, an editor, a guiding leader. Despite her fragile health, Renuka worked with an inner discipline that astonished those around her. Many remember the hours she spent at her computer, shaping each sentence, each page, with quiet intensity.

Even amidst her political responsibilities as a member of the Dandakaranya Special Zonal Committee, she found time to write personal letters to comrades. These letters — filled with insight, gentle critique, and sincere warmth — are still carefully preserved by many. Even those who left the movement keep them safe. That is the kind of imprint she left on everyone who knew her.

In 2014, when her elder brother exited the movement, Renuka was deeply hurt. She opposed his backstep, and wrote to their parents with unwavering clarity: she would never leave the revolutionary path — not until her final breath.

And she never did.

Finally … as a communist revolutionary, writer, and editor — perhaps we, her family, would never be able to fully grasp the depth of her accomplishments. We may never truly understand them all. But the way she grew, steadily and with conviction, and the way she stood firm for what she believed in — Renuka’s life will always remain a source of pride for us.

To end the suffering of the working class, to build a society free of exploitation and oppression, to put an end to gender violence and discrimination, to abolish caste-based injustice and attacks, to stand against religious fundamentalism — these were her dreams. And now, fulfilling them is our collective responsibility.

Her immortality lies in the path she carved out and the lives she touched. She will continue to inspire us; because her death was not just an ordinary passing. As a mother says in one of her stories: “A death that stands tall like a column, right in the middle of the village.”

* ~ *

Gumudavelly Renuka – Beloved Daughter of Kadavendi, Heroic Warrior of the People

– Written by Bhavana

originally in Telugu

Comrade Gumudavelly Renuka’s life is an open book. Her revolutionary journey of three decades and her contribution to the revolution can be termed larger than life. Her three decades of revolutionary work is a message of liberation to oppressed women. Comrade Renuka was an unflinching and dedicated communist revolutionary. She was a determined warrior who never feared the difficulties, hardships, and suffering that are an intrinsic part of guerrilla life.

She was also a revolutionary literary soldier of the oppressed masses. She was a wonderful revolutionary writer, essayist, literary reviewer and critic. She served as the editor of various revolutionary magazines. She introduced important progressive and democratic Hindi writings to Telugu readers through her translations. She was a democrat who always called out male chauvinism in the patriarchal society and fought against it dedicatedly and consciously.

Comrade Renuka was like a crimson flame who learned the lessons of revolution as naturally as a toddler drinking milk from her mother’s breast, in the rural areas of Nalgonda and Warangal districts that were the birthplaces of the historic Telangana Armed Peasants’ Struggle. She hailed from the soil of Kadavendi, where once the masses heroically fought against the landlords of Visnoor and where the first martyr, Doddi Komaraiah, shed his blood.

Renuka’s birthplace, Kadavendi, gave birth to many other revolutionaries. When we think of Kadavendi, the first name that comes to mind is Doddi Komaraiah; in the generations that followed, it is Paindla Venkataramana and Arramreddy Santosh (Mahesh) — and now, Renuka, who carried that legacy forward with unwavering commitment until the very end.

Renuka’s family was not just among those innumerable families who aspired for revolution, but one that sacrificed their beloved daughter for the revolution. With Renuka’s martyrdom, Kadavendi turned even redder. Her funeral procession will leave not just an indelible impression in the history of Kadavendi village, but will also add a new chapter after Comrade Santosh’s martyrdom. In the history of this village, she is the first-ever woman leader of the revolutionary party to attain martyrdom.

Comrade Renuka was murdered on March 31, 2025, in yet another fake encounter in Belnar village of Bijapur district (Indravati area) by the police. Her mortal body was taken to Kadavendi by her family members and friends. Our revolutionary salutes to those thousands of lovers of the revolution who, on the 2nd of April, lent their shoulder to carry her in her final journey; to those thousands of revolutionary sympathisers, writers, artists, intellectuals, social activists, journalists, activists of women’s organizations, and those fellow travellers who had travelled and are continuing to travel along with Renuka in the revolutionary movement, who participated in her final march; to those people from neighbouring villages who turned the village into a sea of red flags; and to those who walked in the procession with affection for their beloved daughter and with much love in their hearts for the revolutionary movement and unflinching confidence in the victory of the revolution.

All those thousands who took part in the funeral procession of Renuka held red flags, placards and banners and rent the air with slogans such as “Stop Operation Kagar Now,” “Stop Fake Encounters,” “Red Homage to the Martyrs,” “Let’s Continue the Lofty Aims of the Martyrs,” “When One Warrior Falls, A Thousand Will Rise,” and so on. The procession was accompanied by drum beats, revolutionary songs, and the fluttering of red flags. The collective grief and anguish and anger felt by all in the procession is shared by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in one of its statements.

It also expressed condolences to her parents, siblings, relatives, and friends. The void left by Renuka’s absence in their lives can never be filled. But we hope and trust that they will be able to see Renuka in the hundreds of other daughters and sons who stand firmly with the revolution, and that they will continue in the revolutionary camp, offering their cooperation and remain firmly on the side of the oppressed masses.

Let the defiant challenge issued by Renuka’s heroic mother, Yashodamma, to the Indian Constitution inspire us all — to stand firm and continue the struggle for a society where such deaths have no place.

Renuka wrote under several pen names. Most of her work was published in Telugu magazines like Arunatara, Veekshanam, and Mahila Margam. When she was in Dandakaranya, she wrote under the pen names BD Damayanti, and Midko — mostly individually, and a few jointly with another writer, Aman. Before we go into the details of her long revolutionary journey, let’s take a look at the revolutionary ideas that she put into words through her writings at various times.

“Remembering March 8 is neither a festival nor a celebration. It is a commitment to continue the struggle of women who have fought for generations. It is about passing on that struggle to future generations in an even more inspiring way. The ruling classes, who try to protect their power by inflicting cruel violence on women, are not qualified to speak about March 8th or women’s empowerment. March 8 is an apt opportunity to expose and tear down their anti-woman facade.”

(Written on the occasion of March 8, 2012: “Let’s raise our voices along with the oppressed women of the entire country against the state violence perpetrated on women.”)

“If this war is not stopped here and now — in this land that is the abode of ancient human societies, that is home to a great culture and rebellious tradition — if we don’t raise our voices loudly and shout out with all our strength that this onslaught must be stopped immediately, we will not be able to preserve our country and its natural wealth. This is not merely a question of the existence of the nameless Adivasi people of the Maad area; it is also a question that concerns the future of our country.”

(From her article written in 2012 for Veekshanam under the name Chaite Madavi: “Destructive attack on Maad area by the state armed forces”)

“The students’ demand to include beef in the university hostel mess is actually a very small one. It is natural for people to want to protect their right to eat the food they like and to expect respect for their food habits. This is also about self-respect. But still, a big fight and a major cultural struggle is happening over this simple issue. In the areas where the revolutionary movement is active, people’s food habits are not just protected — they are owned by the movement with pride. The movement supports the people who are standing up for their rights. In this way, it protects their self-respect. This can only happen by carrying on an ideological fight against the communal thinking of Hindutva and by educating and raising the consciousness of the people.”

(Written in 2012 under the name Midko, in solidarity with the students fighting for the inclusion of beef in the menu: “How the food habits of the oppressed people are being preserved by the revolutionary movement”)

“A brigade-sized Indian Army unit that arrived on the pretext of training has now stationed itself on the periphery of Maad area. Although they are using training as a pretext because they are mindful of the resistance from the people of this country, it is not difficult to understand that the Army has actually come here to unleash war against the people… Today, the ruling classes of our ‘Independent’ India are sending their army against the poorest of the poor, who live in the heart of the country, in order to implement their pro-corporate, neoliberal policies without any hurdles. It may be true that the army of the White rulers could suppress the Bhumkal rebellion in the past. But it is also a historical truth that events in history do not always repeat in the exact same way.”

(Co-written by B.D. Damayanti with Aman in 2012 — ‘Bastar People Marching on the Path of Bhumkal’)

Between 2005 and 2007, both the central and state governments, along with top military leaders and notorious leaders known for brutally suppressing people’s movements, unleashed a wave of white terror in Dandakaranya in the name of Salwa Judum (mass hunt). During this violent campaign, which was falsely presented as a peaceful movement, Renuka carefully documented the attacks, torture, and brutality faced by the poorest and most oppressed people in a book by visiting the affected areas herself and speaking directly with the people. The book is titled ‘Pachani Batukulapai Nippai Kurustunna Rajyam’ (The State That is raining Fire on Thriving Lives) and she wrote it using the pen name of B.D Damayanti.

That murderous campaign was led by the notorious tribal landlord, most opportunist politician, and former Minister of Industries in Chhattisgarh government, Mahendra Karma — who acted as the trusted commander-in-chief for the oppressive ruling classes. Renuka’s writing, based on her field visits and first-hand observations, detailed the atrocities of Salwa Judum in a manner that has hardly been matched by any other work that came to light!

Another piece of writing that came from Renuka’s pen in 2012 was ‘Vimukti Batalo Narayanapatna’ (Narayanapatna in the Path of Liberation) which gave a written form to the people’s movement that rose from the jungles of Koraput district in Odisha between 2004 and 2010. The Adivasi masses, who were disillusioned with the hollow politics of modern revisionists, broke those shackles and forged ahead through their militant struggles and with the slogan ‘land to the tiller’. Renuka’s book is a short introduction to the experiences, struggles and sacrifices of the oppressed masses who heroically reclaimed hundreds of acres of agricultural land from the landlords.

Comrade Renuka wrote in many forms — starting with short stories, and moving on to essays, reflections on people’s struggles, book and film reviews, pamphlets for different occasions, life sketches of martyrs, profiles of comrades in the movement, and interviews. The Party gave her the important task of documenting the experiences of guerrillas from Battalion Number 1 who were injured in various battles since its formation in 2008. She was very keen to complete this task. However, due to the increasing intensity of the enemy attacks, she could not find the opportunity to conduct the field studies necessary for this task. It is no exaggeration to say that, apart from those who were martyred, almost every guerrilla in that battalion had been injured in one battle or another.

The revolutionary spirit in her writing, her words forged through class struggle, her strong belief in democratic values and socialist ideals, and her efforts in the literary field to reflect the political, economic, and social hardships faced by the people — all of these can become valuable material for future researchers to study and possibly turn into a book.

Comrade Gumudavelly Renuka (54) spent about three decades of her life in the journey of the revolutionary movement. She was born in Kadavendi village of the old Warangal district. Her mother is Comrade Jayamma (Yashodamma), and her father is Comrade Gumudavelly Somaiah. Renuka is the second of their three children; she has an elder brother and a younger brother. Comrade Somaiah is a retired schoolteacher. Her parents are progressive thinkers, and the revolutionary movement has had a deep impact on their children. Apart from the influence of the Telangana armed struggle, Comrade Somaiah was greatly inspired by the revolutionary movement that steadily gained strength in Warangal district in the late 1970s. It would not be an overstatement to say that, except for the oppressive and landlord classes, hardly any family in that village remained untouched by the revolutionary movement — and Comrade Somaiah’s family was one of them.

Comrade Renuka studied up to the 7th class in her own village, Kadavendi. She completed her 10th class in Mothkur of Nalgonda district, and then pursued her intermediate education in Jangaon. After completing intermediate, her parents arranged her marriage. Although she had a strong desire to pursue higher education, she could not go against her father’s wishes. However, when she faced oppression and humiliation in that marriage, she soon walked out of the toxic relationship and resumed her studies. In 1992, she secured a seat in the law course at Padmavati University in Tirupati. After graduating, she briefly practised law under the guidance of a senior pro-people lawyer.

Although Comrade Renuka was born in the rural areas of Warangal district, which was called a bastion of revolution, and learned about revolutionary movements from early childhood, she came into direct contact with the then CPI (ML) [People’s War] only in 1992 in Tirupati. At that time, the popular revolutionary activist and martyr Comrade Padmakka was handling organizational responsibilities in Tirupati. She was organizing students, women, and employees in that town, especially guiding a revolutionary women’s organization. Soon after meeting Renuka, Padmakka encouraged and guided her to work in that organization. Comrade Renuka gladly took up that responsibility and involved herself in the revolutionary work of organizing urban women, students and working-class women.

She soon became a party member and then the secretary of Tirupati party cell. She worked in that town until 1999. By 1998 itself, she was recognized by the party as an area-level organizer. In view of her interest in literature, her passion for writing, her ability to study any issue in depth and analyse it, and sharp critical outlook, Comrade Renuka was brought onto the editorial board of that women’s organization’s magazine.

In 2000, Comrade Renuka moved from Tirupati to Visakhapatnam as per the party’s requirement. There too, she took up responsibilities in the local women’s organization and began implementing organizational tasks alongside comrades already working there. She became part of the city committee in Visakhapatnam.

As she actively and creatively carried out the responsibilities entrusted to her by the Party and worked with commitment, her dedication towards politics of class-struggle strengthened. Additionally, her sincerity, discipline, democratic approach in convincing others patiently, her deep study of Marxism, and her strong political interest were recognized by the party. Taking all of this into account, in 2003, the party elevated her as a district-level cadre.

Regarding her personal life, in 1997, Renuka married Comrade Arramreddy Santosh (Mahesh), who was then the secretary of the Andhra Pradesh state committee and a central committee member. Since Renuka was then working openly while Santosh was under intense state surveillance, the party decided that their marriage must remain secret. On 2nd December 1999, Mahesh was killed by the state, along with Shyam and Murali, through betrayal by a covert. His martyrdom was a massive shock to Renuka, and it took her a long time to recover from the grief.

In 2003, while Renuka was working in Visakhapatnam, her fellow committee members, Comrades Kaumudi and Janardhan, were captured and killed in fake encounters by the police. Around the same time, a PLGA ambush on the then Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, N. Chandrababu Naidu, carried out in Tirupati was partially successful. Soon after, a large-scale manhunt was launched in the Rayalaseema and Coastal districts. For those revolutionaries who were already under police surveillance, the scope of open work shrank drastically. Although Renuka had no direct or physical link to the ambush, she had to go underground and begin working among the people in a new region.

In her underground revolutionary life, Comrade Renuka first moved to the Bansdhara area of Andhra-Odisha border zone. There, she quickly connected with the Kui Adivasi people living in the lap of nature. She worked as a member of the Bansdhara divisional committee until the end of 2005. Though the life in forests and mountains was unfamiliar to her, and she had no previous exposure to the Kui tribals, she embraced the region and the Kui language with the help of other comrades. Realizing that understanding the politics of Odisha and explaining it to the local people required learning the Odia language, she put great effort into learning that as well. Renuka always believed that revolutionaries could only integrate with local people by learning their language and customs. With that understanding, wherever she went she worked hard to learn the local language of the people and to understand and adapt to their customs.

While working as the DvCM of the Bansdhara division, Comrade Renuka also took up the responsibility of serving as a member of the AOB zone Women’s Sub-Committee, formed to study women’s issues and suggest recommendations. These committees were expected to study the issues faced by women in the following four fields and put forward their recommendations to the Party to resolve those issues: (1) the political, organizational, and military challenges faced by women in guerrilla life, including the effects of male domination and patriarchy; (2) the political and organizational problems encountered by women activists and women leaders of various committees within the party, along with the impact and pressures they faced from male domination in those roles; (3) the organizational difficulties faced by women in mass organizations, again shaped by patriarchal attitudes in the society; and (4) the multilayered oppression experienced by working-class and all the oppressed women in broader society, including within the family, tribe, caste, and the state — combined with persistent male domination and discrimination. At the same time, the committees were expected to strengthen their ideological understanding that patriarchal society is the root cause of all these issues. As a member of the sub-committee, Comrade Renuka worked tirelessly to study and address all these dimensions with deep commitment.

Despite being new to life in the forest, living among guerrillas, and understanding the lives of Adivasis, she made every effort to understand the problems of all with a deep sense of responsibility. She would engage in discussions with them to find resolutions to those problems and instill self-confidence among them. On the other hand, she would bring these issues into party committee discussions, participate in making the right decisions, and contribute to shaping appropriate forms of struggle and organizational structures.

Comrade Renuka also took up the responsibility of serving as a member of the editorial board of the women’s magazine ‘Viplavi’, which was being published in the AOB zone during those days. As the revolutionary movement advanced, not only was women’s participation rising, but a militant women’s movement was also taking shape. This gave rise to the need for a dedicated magazine for women — a platform to serve as an organizer, to help improve their understanding across various fields about the challenges they faced due to patriarchal society and male domination. Comrade Renuka, who always had a deep interest in writing, played a vital role as part of the editorial board. She worked hard to bring ‘Viplavi’ in a creative and engaging manner that would appeal to its readers. Alongside this, she also played a key role in bringing out a book of life sketches of the women martyrs from the AOB region who laid down their lives from the beginning of the movement in that region up to that point (1980–2005). It was her initiative that led to inviting a veteran woman comrade from the older generation — someone who lived as though revolution was her very breath — to write the foreword for the book.

The Party’s state committee, taking into consideration Comrade Renuka’s potential, her interests, and the kind of tasks she was already undertaking in the region, felt that to utilize her services more widely, effectively, and meaningfully, she should be moved to the press unit run by the Central Committee. Responding positively to this proposal made by the state committee, the Central Regional Bureau inducted her into the editorial board of ‘Kranti’ magazine.

Kranti used to be the official political organ of the Party’s Andhra Pradesh state committee and served as a beacon light for the Indian revolution in the 1980s. However, after the movement in Andhra Pradesh suffered a temporary setback, the responsibility of Kranti was taken up by the CRB, which continues to run it till today. Comrade Renuka became part of the Kranti editorial board in 2006 and continued in that role until 2012. As part of that responsibility, she stepped into Dandakaranya forests in the beginning of 2006.

That was a very crucial time for the revolutionary movement. While the movement in the three regions of Andhra Pradesh (North Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and AOB) was facing a temporary setback, in Dandakaranya, the fascist ‘Salwa Judum’ had unleashed white terror on Adivasi masses, followed later by ‘Operation Green Hunt’. Salwa Judum split many Adivasi families vertically, creating major turmoil in their lives and turning entire villages into graveyards.

By 2009, as Salwa Judum was defeated through mass resistance, the oppressive ruling classes of India launched another countrywide attack under the name of ‘Operation Green Hunt’, further intensifying the onslaught. During this time, hundreds of progressive, democratic, and revolutionary mass organizations, Adivasi resistance groups, concerned individuals, rights activists, writers, artists, intellectuals, journalists, and leftist forces not only condemned this onslaught but also exposed it as a ‘war on the people’. Under these circumstances, Comrade Renuka continued her work holding the gun in one hand and the pen in the other, proving herself to be a brilliant literary soldier.

During those days, to undertake a field study of the fascist terror unleashed on the people of Dandakaranya — especially in the south and west Bastar regions — Comrade Renuka visited several villages and met hundreds of families of the victims, taking upon herself immense personal risk. She listened to the unspeakable, appalling sufferings that poured from the depths of people’s hearts. She not only listened to them with deep empathy but transformed their anguish into words with her powerful pen, producing an important report titled ‘Mandutunna Gaayaalu’ (Burning Wounds).

This study took a personal toll on her; she experienced significant emotional trauma upon hearing the harrowing experiences shared by the people. She could only overcome it by channelling her pain into her writings. In later years, whenever she returned to these villages and met the families — many of whom had since joined the revolutionary movement — she would always ask them about their past experiences of those times. She developed a deep bond with the family of Emla Kovalu, the president of Janatana Sarkar of Mankeli village of Gangalur area, the first martyr killed by Salwa Judum. As his wife and children later joined the movement, Renuka would speak to them often, revisiting those memories emotionally, sometimes even weeping.

At a time when the revolutionary movement was experiencing a serious onslaught, Comrade Renuka also suffered a profound personal loss. In March 2010, her life partner, Comrade Shakhamuri Apparao, was killed by the state in yet another fake encounter. Being a person of deeply sensitive nature, she responded emotionally to the hardships and losses faced by both the people and the party and the revolutionary movement during Operation Green Hunt. It naturally took her a long time to come to terms with the loss of her partner, but she continued her revolutionary work, striving to overcome her grief with the support of her comrades.

Towards the final years of her involvement with Kranti, she proposed studying the people’s movement in Narayanapatna, located in the AOB region. When she presented the proposal, the party too felt it was timely and necessary. Trusting that Comrade Renuka would carry it out with commitment and diligence, the Central Regional Bureau made arrangements for her travel.

Following the setback of the Naxalbari movement in the 1970s, the Lalgarh movement in West Bengal, which arose between 2008 and 2011, drew nationwide attention. This movement pioneered several new experiments in revolutionary practice. Initially started as an anti-displacement struggle, it went on to challenge the state with a combination of legal and armed resistance, all aimed at establishing people’s power. In parallel, during nearly the same period, thousands of Adivasis in Narayanapatna, Odisha rose up to reclaim their land from landlords through militant struggles that echoed the historic Srikakulam struggle of the early 1970s.

To study this uprising, Comrade Renuka embarked on a grueling journey through forests and mountains, crossing multiple rivers and covering hundreds of miles on foot, accompanied by guerrilla comrades. After nearly two months of field work, she published her findings in the form of a book titled ‘Vimukti Batalo Narayanapatna’ (Narayanapatna – In the Path of Liberation), under her pen name B.D. Damayanti, in 2013.

While on the editorial board of Kranti, Comrade Renuka worked directly under the leadership of Central Committee member and martyred Comrade Katakam Sudarshan (Anandanna / Dula Dada), and gained significant experience. Later, after being transferred to Dandakaranya, she served most of the time as in-charge of the press unit under the guidance of another martyr, Comrade Ravula Srinivas (Ramanna), secretary of the DKSZC and also a Central Committee member.

In 2013, due to unavoidable circumstances, the publication of Kranti was suspended for two years. During this time, Com Renuka was reassigned to the editorial board of Prabhat, a quarterly magazine. As Prabhat was published in Hindi as the official magazine of the Dandakaranya Special Zonal Committee, she took on the challenge of learning Hindi. With the support of the editorial team and primarily through her own persistent efforts, she soon reached a point where she could directly write essays and reports in Hindi.

From 2013 until the end of 2024, Comrade Renuka worked primarily in the press unit of Dandakaranya. In addition to managing the publications, she translated several party circulars, documents, and internal party papers from Telugu to Hindi. Being already proficient in the Koya language, she also translated key revolutionary literature into Koya to make it accessible to local cadres.

She frequently undertook field visits to study the experiences of people’s struggles, challenges in mass organizational work, incidents of state violence and repression, and various forms of domestic violence and customary oppression within the tribal society. She regularly interacted with local guerrilla comrades to understand their hardships and concerns. During the field visits, she also engaged with women comrades to gather insights into their experiences, especially those rooted in patriarchal attitudes and male domination. Comrade Renuka was a dedicated literary warrior who transformed her field observations into analytical essays and reports, publishing them in various magazines as required.

Comrade Renuka conducted a special study on the issue of labour migration in the East Bastar division. Her study gained significance following a 2014 resolution passed by the Central Regional Bureau on the issue of labourers migrating from Dandakaranya to various parts of the country. Writing about the problems faced by Adivasis as migrant workers in cities is a challenge for any writer. It is impossible to imagine the exploitation of labour, the sexual violence faced — especially by women — and other forms of deceit perpetrated on them starting from the local contractors who arrange their work placements, to their workplaces in the cities, unless heard directly from the victims themselves. It is not just the pressures and intimidation from employers, but there are also cases where young women had to face sexual exploitation by fellow villagers who travelled with them for work. Comrade Renuka listened to these first-hand accounts and faithfully documented them in a book titled “Pattanalaku Pravahistunna Adavi Biddala Chemata, Netturu (Flow of Sweat and Blood of Adivasis to Cities) – A Study on Migrant Labour from Chhattisgarh’s Forest Areas,” published under her pen name ‘Gamita’.

Comrade Renuka was as gifted in teaching as she was in writing. While continuing with her responsibilities, she taught political classes to guerrillas and party cadres whenever party committees called upon her. In addition to teaching the documents produced by the Party’s Central Committee, she conducted study classes in Koya language for local cadres on the basics of Marxism. Simultaneously, she attended political education classes conducted by higher committees to deepen her understanding of Marxist theory.

In 2011, the Dandakaranya Party Plenum reviewed that the movement had entered a ‘critical’ phase. This assessment came in the wake of significant losses during Operation Green Hunt, a sharp rise in desertions — including from leadership ranks — and a growing number of surrenders to the police. In this adverse situation, the Party launched the Bolshevization Campaign in 2013. As part of this campaign, Comrade Renuka actively participated in the ‘social study and analysis’ programme, which continued in various forms from 2013 to 2018. Leadership comrades prepared study papers on the evolving conditions in different divisions of Dandakaranya, and Comrade Renuka took part in the discussions based on those papers. Her contributions — both in articulating her views and in responding to others’ questions — were always meaningful and insightful and made others in the study camp think seriously about various issues.

While continuing her work in the press unit during this period, Comrade Renuka also trained several new comrades in computer operations, developing them into skilled typists and operators. By 2010 — and even earlier in some regions — the Indian revolutionary movement had suffered setbacks in urban and plain areas. As a result, the Party’s Central Committee was no longer in a position to send fresh forces to Dandakaranya from outside. Meanwhile, because the movement in Dandakaranya had not expanded into non-peasant sections, it increasingly became isolated and limited to Adivasi communities alone. However, with hundreds of new recruits joining the PLGA from these very sections, there arose an urgent need to train them as cadres capable of handling a wide range of responsibilities.

In such trying circumstances, Comrade Renuka took it upon herself to train a number of young Adivasi men and women as computer typists and operators. Many among them had only learned to read and write after joining the movement, yet under her guidance, they became proficient typists with an eye for accuracy. She also mentored them in scanning and digitizing hundreds of books, and helped several comrades acquire valuable experience in printing and publishing work.

After the news broke that Comrade Renuka (Chaite) had been killed, these comrades everywhere remembered her fondly. They took a solemn oath to continue the struggle with greater determination, vowing to fulfil the cherished aims of the martyrs.

At the Dandakaranya Party Plenum held in October 2020, Comrade Renuka was unanimously elected — along with some others — to the Dandakaranya Special Zonal Committee (DKSZC). As part of the tasks formulated by the plenum, the DKSZC revived the Women’s Sub-Committee with the aim of rejuvenating the women’s movement in the Dandakaranya zone. Comrade Renuka became an active member of that sub-committee and continued in it until her final breath. She carried forward the legacy of martyr Comrade Uppuluri Nirmala (Narmada), who had led this committee longer than anyone else and had earned the love and respect of comrades across the ranks, with total commitment.

Comrade Narmada was also part of the first editorial board of Prabhat, along with another martyr, Comrade Aluri Bhujanga Rao (Peddanna). For a time, she led the Dandakaranya (DK) press unit and contributed to revolutionary literature under the pen name ‘Nitya’. Known for her modesty and warm relationships, Comrade Renuka shared a close bond with Narmada, as well as with Narmada’s partner, Comrade Rani Satyanarayana (Kiran Anna), who had earlier served as the in-charge of the DK press. He was later framed in a false case, spent several years in Taloja Jail in Mumbai, and was eventually released on bail.

In this fashion, Renuka saw closely various aspects of Narmada’s revolutionary practice and held deep respect for her. Their camaraderie and shared commitment to the cause reflected in numerous ways throughout their individual and collective revolutionary journeys.

As most members of the women’s sub-committee were from local Adivasi backgrounds, Comrade Renuka played an active role in preparing the agenda, discussing all points in the agenda comprehensively during meetings, selecting suitable essays from Marxist teachers for collective study during the meeting, taking minutes, drafting resolutions, and more. She would also select and recommend appropriate study material to the committee members in order to strengthen the women’s movement in Dandakaranya.

After becoming a member of the women’s sub-committee, she had to work even harder to ensure the regular publication of the Hindi magazine Sangharshrat Mahila, the official organ of Krantikari Adivasi Mahila Sangathan. Furthermore, when it was decided that this magazine should also be published in the Koya language under the name Lademayena Mahila, Comrade Renuka once again played a key role in implementing that decision. She was the kind of comrade who, no matter which field she was given responsibility in, would do complete justice to it.

With her demise, the women’s movement in Dandakaranya has lost a trustworthy, reliable, and beloved leader. Her absence can only be addressed by relentlessly working in the light of the lessons she taught us, guided by her ideals and cherished aims — and by continuing to march forward, even amidst repressive offensives like Operation Kagar, and those that may be even more severe.

Let us also briefly discuss Comrade Renuka’s health. There was, undeniably, a sharp contrast between the conditions of her early life and those she faced during her guerrilla life in the forests. While in the Bansdhara area — and later, post-2006, in Dandakaranya — she was frequently afflicted by malaria, including several bouts of falciparum malaria. The symptoms were intense. At times, she would suffer such severe headaches that it felt as though her nerves were splitting. She also endured chronic spondylitis.

Yet, despite all of this, with a 30-carbine slung over her shoulder and clad in olive green uniform, she marched on alongside her guerrilla comrades. Every time one saw this thin-framed woman climbing up and down the hills, Lenin’s words would come to mind: “The belief that the path we have chosen is right intensifies revolutionary spirit and enthusiasm a hundredfold to create wonders.”

Having embraced revolutionary life in 1996, Comrade Renuka endured a series of deeply personal shocks between 1999 and 2014 that left her emotionally shaken. Yet, with unwavering resolve and the support of her comrades, she overcame those. Despite significant physical challenges due to ill health, the final decade of her revolutionary journey was undoubtedly her most remarkable and productive — marked by tireless commitment and boundless enthusiasm.

The stories written by Comrade Renuka were published in Viyyukka, an anthology brought out by Virasam (RWA) in 2023. As soon as the Revolutionary Writers’ Association announced the anthology, Comrade Renuka was among the women writers of Dandakaranya who immediately responded to the announcement. After carefully reviewing the list of stories, she wrote a letter to the editors, pointing out which were hers and which were not, despite being published under her name. She also identified the true authors of a few stories she recognized. Tragically, this letter, written with the intent of reaching Viyyukka’s editors, turned out to be her last.

And this is what Comrade Renuka wrote in grief when her young comrade from the DKSZC committee, Comrade Rupesh, was martyred:

“We suffered a lot of losses in a series of enemy attacks. But until now, they had not succeeded in targeting CC and SZC leadership. This time, the enemy has achieved that. In the current situation of the Gadchiroli movement, Comrade Rupesh’s martyrdom is not just a loss to that region but to the entire Dandakaranya movement. It is tragic that we lost a comrade who possessed many capabilities including military capability, who is trustworthy and has deep-rooted commitment to revolutionary values. He was one of the most reliable young leaders — principled, steadfast, and a man of great ideals. The loss of a local comrade like him will deeply affect both the cadre and the people. He was someone who could go wherever needed and take up any revolutionary task. His absence will weigh heavily on our tactical decisions going forward. As I don’t know much about the others who were martyred alongside him, I can’t yet say how their loss will impact us.”

Even amidst the series of Kagar attacks, Comrade Renuka continued to fulfill her responsibilities with unwavering dedication. When, on April 16th, 2024, police killed 29 comrades in a brutal attack on a guerrilla unit near Apatola-Kalpar of North Bastar, she was nearby, carrying out her duties. The massacre shook her deeply — not only did she know many of the martyrs personally, she had spent time with them just days before. The police captured some of the unarmed comrades alive, forced them to carry the bodies of their fellow fighters to the waiting vehicles, and then executed them. Comrade Renuka was devastated by this cruelty, and she condemned the massacre with righteous outrage. She worked tirelessly to communicate the details of the martyrs to the outside world.

Again, on June 14th, 2024, police launched another attack on a guerrilla unit in Kodtamarka of the Maad area. Comrade Renuka, who was present nearby, escaped narrowly. In the course of the year-long Kagar military offensive, from January to December 2024, she painstakingly documented each martyr’s details and publicized them to the outside world. In August 2024, she compiled all of this into a book — a lasting testament to her leadership and editorial commitment that will remain etched in the annals of Dandakaranya’s revolutionary history.

Here’s what she wrote during that time about the situation her unit was facing under Operation Kagar:

“Some of our members are falling ill with malaria frequently. But we don’t even have chloroquine tablets. I don’t know what to do. Please send us some general medicines if possible. My own medications, which I’m supposed to take regularly, were exhausted while I was in North Bastar. I wrote to the comrades there before returning, and I also wrote again to another comrade after reaching here — but the medicines haven’t come through from either side. In the present situation, asking them repeatedly for medicines feels like not understanding the gravity of their own conditions, isn’t it?”

The Kagar military attacks are not only disrupting the lives of revolutionaries but also devastating the lives of ordinary Adivasi people. The rulers of this country want their forests. They want India’s economy to rise quickly to the third-largest in the world. They want a ‘Viksit Bharat’ by 2047 and to make India a haven for foreign capital.

To achieve all this, they need to plunder the massive natural wealth locked within the forests, especially in areas where Maoist revolutionary movement is strong. For that to happen, they want Maoism wiped out. They don’t want Maoists in the forests. Urban Maoists, being even more dangerous in their view, must also be eliminated. In the eyes of the state, anyone who questions is a Maoist. No one is to be spared.

This is the kind of state that murdered Comrade Renuka on March 31st, 2025, in a most brutal manner. And yet, no Kagar will ever be powerful enough to silence the slogans that echoed across Kadavendi, amidst a sea of waving red flags. Those slogans will surely be transformed into a material force.

The massacres did not end with the murder of Comrade Renuka. Her martyrdom is neither the first in India’s great revolutionary movement, nor, despite our deepest hopes, will it be the last. Renuka remains an unyielding flame on the path of the Indian people’s democratic revolution. Despite suffering from ill health, she was making efforts — alongside another comrade from her committee — to initiate ‘peace’ talks with the government, hoping to at least temporarily halt the massacres unleashed by the ruling classes. It was while she was in this pursuit that she was killed.

Just as Comrade Cherukuri Rajkumar, the party’s spokesperson, was murdered during Congress rule while pursuing peace talks mediated by Swami Agnivesh, now the saffron-clad fascists have murdered Comrade Renuka in a similar staged encounter. Her sacrifice once again exposes the hollow rhetoric of peace and non-violence propagated by the ruling classes. They dragged her out from her shelter, and shot her in cold blood on the banks of the Indravati River.

Her murder lays bare the savage character of the fascist Hindutva regime. It reaffirms the truths Comrade Renuka consistently raised in her writings, and highlights the grave threat the country faces from these Hindutva forces. The true homage to Comrade Renuka lies in carrying forward her ideals and realizing the goals she held close. No amount of Kagar campaigns or missiles can ever extinguish the fire of revolutionary thought she embodied.

Comrade Renuka’s martyrdom is undoubtedly an irreparable loss to the revolutionary movement. Especially at a time when the revolutionary party has recognized the serious mistakes that took place over years of prolonged practice and has begun the process of correcting them, her absence leaves a painful void. Reflecting on the Party Polit Bureau’s circular, she offered her sharp observation thus: “We took these decisions far too late — only after the damage had already been done. Had they been made earlier, they would have made a real difference.” Alongside this, she shared numerous critical insights with the party’s higher leadership, who acknowledged that her views were thoughtful, necessary, and worthy of implementation. Now, it is the responsibility of the revolutionary movement to carry forward this process of rectification without Comrade Renuka — a comrade known for her unwavering determination and exceptional capabilities. Let us step forward and continue the work she left behind.

Comrade Renuka’s writings burned with the intensity of lived experience and revolutionary purpose. They were not just words — they were a call to action, written with the same conviction she carried into every battlefield, gun in one hand and pen in the other. Her martyrdom marks a luminous chapter in the history of the revolutionary movement — one that will continue to inspire generations to come. The intellectual strength and clarity she cultivated through years of commitment enriched the struggle in profound and lasting ways. She was not merely a dreamer of revolution — she was a fighter who dedicated her life to realizing that dream. She will be remembered as the voice of a new dawn.

* ~ *

Today is Our Chittamma’s Birthday!***********************************

Today marks the 55th birthday of our Chittamma, known to the world as Gumudavelly Renuka. As she is no longer with us in person, perhaps it is more fitting to observe it as her birth anniversary from now on. It has been 22 years since she left our home. Every October 14, throughout these years, our mother has cooked payasam for everyone, and the day passes in remembrance — in sorrow, in pride.

We wonder — if she were alive, how would she have celebrated her birthday in Dandakaranya, among her revolutionary comrades? There would be no cakes to cut, no parties — such things do not belong in the life of a revolutionary. Yet, as a writer, a revolutionary, and someone deeply loved by so many, what would our Chittamma truly have done today?

Perhaps she would have risen before dawn, before the darkness faded, and sat for a while on her polythene sheet — the one guerrillas use for everything: to sleep on, to sit and read, to rest their backs, or to talk. It is usually about six feet long and three feet wide.

Sitting there, she would first have remembered her mother and father — thinking, with a mix of sorrow and wonder, “It’s already been 22 years since I last saw them.” She would have sighed, recalling that it had been 11 years since she last wrote them a letter. Her heart might have ached, wondering how they were faring in their old age.

She would have remembered her life-companions, Santosh and Shakhamuri, both martyrs — and reflected on how their brief, tragically ended companionship had filled her with strength and inspiration.

If circumstances permitted, she would have bathed early that morning and chosen the neatest, cleanest clothes from whatever limited wardrobe she carried in her backpack. She would have gone to the kitchen to see what her comrades were preparing for breakfast, and whether there were ingredients for a dish she liked. If there were, she would have joined in — whether or not it was her turn for duty — cooking something to bring joy to her comrades.

Yet she would not have spoken of why the day was special for her. If there were close friends who knew her well, she might have shared a quiet word with them. And if someone noticed her unusually bright expression and silently asked, “What’s the matter?” she might simply have smiled.

Softly, she might have said, ‘Looks like I’ve turned 55 today…,’ her trademark smile spreading gently across her face.

Her comrades, too, would have shared her happiness without any fuss — perhaps with a firm handshake or a warm hug. Maybe someone would have quietly placed a new pen or a little diary into her hands, or offered her a piece of biscuit, breaking it with care.

Then she would have turned her thoughts to the day’s work — the tasks ahead, the ones she preferred, and perhaps choosing her favorite first. Or she might have sat down to read a beloved book — an anthology of poems, or an old text she had scanned and saved on her laptop.

She might have tried to begin the story or essay she had been struggling to write for long. She would have played her favorite Vimalakka’s song, “Adivasi Aatmabandhuvu Edikellene…,” at least twice that day.

If she visited a village that day and saw mothers with little children, she would have lifted a baby into her arms, holding it close, kissing it tenderly.

No matter how busy she kept herself, the day would have brought back endless memories of Kadavendi, her native village — of her childhood, her family, her loved ones. Kadavendi, Mothkur, Tirupati, Visakhapatnam, Bansadhara (Odisha), South Bastar, West Bastar, Abujhmad… she would have recalled every stop in her 55-year journey.

Even after 21 years in the forest, she might have marveled that she was still alive — though with only modest health. She would have smiled to herself, thinking, “Those who once teased me at home and in the village, calling me delicate and soft-hearted, would be surprised to see how strong I’ve become.”

As a storyteller, writer, and activist, she might have quietly reviewed her own journey — feeling a trace of pride at what she had accomplished and the recognition she had earned. A faint smile would have appeared across her lips, almost without her realizing.

But the next moment — the hardships, losses, challenges faced by the movement, the grief of separation, the tears, the martyrdom of beloved comrades — all would have flashed before her eyes like scenes from a film, and that smile would have faded. Her face would have lost its glow.

After a long, tiring day, when her restless mind and weary body finally sought rest, she would have lain down on her polythene sheet, perhaps thinking once more about how her journey had begun and the turns it had taken.

She would have remembered the first novel she read back in Kadavendi, in sixth grade — Mother. She might have smiled again, recalling how, decades later, she reread it and even wrote a commemorative essay when that world-famous novel turned a hundred years old.

She would have recalled the unexpected response her early stories, like Bhaavukata and Viddurapu Manishi, had received — and the inner struggles she faced as she entered the circle of revolutionary writers. While growing up as a revolutionary, she also nurtured the storyteller within her, sometimes confused, sometimes tenderly persistent in her innocence.

Then she would have remembered Santosh, her first life partner, who read every story she wrote and praised them with genuine warmth — patting her back and saying, “Comrade, you’ve found your voice as a storyteller. Proceed.”

She would have smiled, recalling their first handshake in the Nallamala forests, and how, after returning to her room in Tirupati, she went two whole days without bathing — she, who usually bathed twice a day — just to hold on to the sensation of his touch. She even ate her meals carefully, using spoons, not wanting to wash away that feeling.

Remembering those first days of love in the revolution, she might have blushed shyly to herself. She might have remembered their last meeting — on August 2, 1999, at the Kanchipuram bus stand, when Santosh said, “This time, it might take long for us to meet again.”

She could never have imagined that “long” would mean a lifetime. In that silence, her heart would have wept once more. As warm tears slipped down her cheeks, she would have slowly drifted into a restless sleep.

(Written by her family members — Gumudavelly Somaiah, Jayamma, Prasad & Raju — on the occasion of her 55th birth anniversary, 14th October 2025 – published in Telugu by a newspaper – https://www.andhrajyothy.com/2025/editorial/remembering-renuka-midko-a-revolutionarys-silent-birthday-in-the-forests-1456236.html )